Goldilocks Maintenance Strategy: How Being ‘Just Right’ Can Halve Budgets

So often, we confuse efficient with effective.

Several years ago, I was travelling across the US and toured a manufacturing plant. A maintenance team member, talking me through the function and reliability of their equipment, said something that has stuck with me ever since. At a pump of interest, he announced, “This pump here fails around every 6-8 weeks. We can now change out the pump incredibly fast, just like a formula 1 crew”. Whilst an amusing and impressive picture, one he was proud to share, this is a familiar story we hear in industrial plants across the globe.

Maintenance teams are often so time-poor and under-resourced that instead of being recognised or rewarded on how effective they are, they’re measured on conformance to schedule and cost. As I saw, teams are often so used to reacting to equipment failures that stopping to investigate why equipment is failing, or how the failure could have been prevented or detected earlier, just isn’t on their to-do list.

We hope to change that. And of all places, the solution lies in a children’s fairy tale.

We’re all familiar with the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears. A young girl, Goldilocks, stumbles upon a house in the forest. She enters, and to her delight finds three bowls of porridge. The first one she tastes is too hot, the next too cold, but the third one’s just right, so she eats it all up. In maintenance, we too don’t want to react to failures too early (hot) nor too late (cold). So what maintenance strategy is ‘just right’?

Many organizations today maintain a philosophy of regular and scheduled maintenance, and for good reason. This concept was developed in the early 1940s during the second world war when planes were quite literally falling from the sky. British engineers suggested that regularly servicing the planes may prevent them from failing – and ta-da! The age of preventative maintenance was born. It was a novel concept that had merit, worked effectively and quickly gained adoption. But that was 80 years ago! We’ve evolved, our equipment has evolved, so why hasn’t our maintenance strategy?

This approach is just ‘too hot’. Yes, under a preventative maintenance strategy, breakdowns are averted, but at what cost? Preventative maintenance programs can waste enormous amounts of operational and capital expenditure on unnecessary maintenance. John Moubray, cited as the Father of Reliability Centered Maintenance (RCM), pointed out that 40%-60% of preventative maintenance tasks add little value. A recent client visit of mine proved this to be true. They revealed that across just two of their manufacturing plants, they had over 50,000 preventative maintenance tasks. I asked how effective these tasks were, and his expression said it all. I’m sure he (and I) aren’t the only people to question this approach. Every time you have your car in for a regular service with the auto dealer, have you ever asked yourself, ‘Did it really need it?’. Are they replacing or servicing a part that doesn’t require it?

So, if preventative maintenance is too hot, and reactive maintenance by nature is too cold, what’s ‘just right?’.

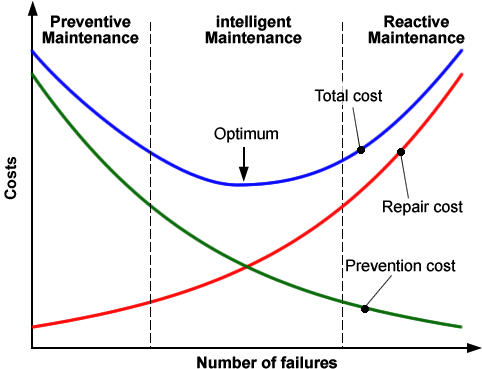

This question was answered in 1988 (which doesn’t seem that long ago, says the 52-year-old). Juran and Gryna, big names in the field of quality management and engineering, proposed that there is an “optimum” target quality level where the sum of prevention, appraisal, and failure costs are at a minimum. Ever since, maintenance professionals have judiciously used Juran’s model to demonstrate that Goldilocks might have been ‘onto something'.

As you can see by the chart above, there’s an optimum point where a balance has been reached, the balance between maintaining ahead of need and maintaining too late. This ‘just right’ is condition-based maintenance. So, the logical question is, how much can you save by adopting a condition-based maintenance approach, a.k.a. the ‘Goldilocks Maintenance Strategy’?

As it turns out, condition-based maintenance costs 50% less than reactive maintenance.

According to the US Department of Energy, each strategy can be averaged out using a simple formula of horsepower [HP] per year. This is what they found:

Reactive Maintenance = $18/HP/Year

Preventative Maintenance = $13/HP/Year

Condition Based Maintenance = $9/HP/Year

A 200 HP motor versus a 5 HP motor will obviously have a proportionately higher maintenance cost. So clearly, changing the strategy yields a significant return. Maintaining only when needed is a winner!

So, how do you start down this path?

Before you run out and start buying up sensors to kick off your condition-based maintenance strategy, here are a few steps to get you started.

- Ensure that your asset management system is up to date with all machinery in your plant. Understanding your plant and machinery is crucial to building the appropriate strategy.

- Prioritize your machinery based on criticality (if you aren’t sure how to start this, please drop us a note, and we can help). Focus on what is important and invest there.

Importantly, not everything can or should be placed on a condition monitoring strategy. Understanding the criticality is important, but which strategy to apply, is key. The table below may shed some light.

Maintenance Priority Matrix

Weighting |

Description |

Application |

| 1 | Emergency | Life, health, safety risk-mission criticality |

| 2 | Urgent | Continuous operation of facility at risk |

| 3 | Priority | Mission support/project deadlines |

| 4 | Routine | Prioritized: first come/first served |

| 5 | Discretionary | Desired but not essential |

| 6 | Deferred | Accomplished only when resources allow |

Source: Section 5.6. How to Initiate Reliability Centred Maintenance. Operations & Maintenance Best Practices - A Guide to Achieving Operational Efficiency (Release 3.0), 2010.

Finally, once you have established your criticality assessment, you are in a position to assign which strategy to select; again, here is where suitability applies.

Reliability-Centred Maintenance Hierarchy

|

|

Preventative Applications |

Condition-based Applications |

| Small parts and equipment | Equipment subject to wear | Equipment with random failure patterns |

| Non-critical equipment | Consumable equipment | Critical equipment |

| Equipment unlikely to fail | Equipment with known failure patterns | Equipment not subject to wear |

| Redundant systems | Manufacturers recommendations | Systems whose failure may be induced by incorrect preventative maintenance |

In summary, we believe that Condition-Based Maintenance is the ‘Goldilocks Strategy’ which can be used cost-effectively with the right type of equipment. Knowing how a machine will likely fail (or has failed before) is also a great place to review your maintenance strategies. Understanding the P-F Curve (in sickness and in health) is where we’ll begin in the next article.

References

Cover image sourced from: https://wilsonallen.com/resources/blog/the-goldilocks-principle-getting-your-software-implementation-just-right

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Cost-associated-with-traditional-maintenance-strategies_fig1_271456155